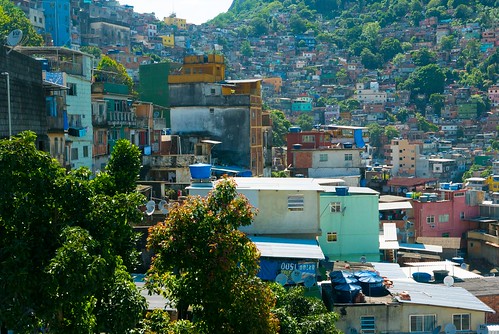

The English translation of favela is “slum”; 20% of the

Brazilian populace live in them and there around 1,000 in the country. They are

often portrayed in the media as drug-riddled no-go zones controlled by gangs,

where tourists are robbed (or worse) if they step foot in them. The reality is

a lot more complex as we found out when we joined a favela tour the next

morning. Aiming to dispel some of the myths surrounding Brazil’s poorest areas,

our guide Marina took us to Rocinha, Brazil’s largest favela with a population

of over 80,000 people. Favelas grow organically – from shacks made of bits of

wood and sheet metal up to fully constructed buildings; because the law states

that if you occupy public land for 5 year it’s yours, and because the

government want little to do with the favelas, they’ve grown largely unchecked. It also helps that a lot of the residents of favelas have come from the construction industry so are well-versed in throwing up buildings with a modicum of structural integrity. Apartments appear overnight next to each other – it’s a regular occurrence to

be able to look out of a window over the bay one day, and the next to be faced

with a brick wall where a new neighbour has taken it upon themselves to erect a

new property.

Only in the last decade or so have the police begun to take

the drug crime seriously and actually do something about it. A process of

“pacification” has taken place in 39 favelas so far where, after a lengthy

observational period (often a year or more) tracking the movements of the drug

gangs and understanding the layout of the favelas - which have no street names in most cases - a co-ordinated effort of thousands of police descend on the favelas and

wrest control back. Most of the populace

don’t want drugs in their neighbourhoods anyway, so pacified favelas are much

happier places. As Marina told us, there’s a difference between poverty and

misery, and whilst life is often tough, many of the residents won’t go

elsewhere. They are self-governed communities, most with family and friends who

have lived there for some time, they police themselves, and they are incredibly

entrepreneurial. Favelas don’t pay taxes, and we visited one building where the

owner had built floor upon floor of apartments and was renting them out at 700

reais (~£130) per apartment, and bringing in around 30,000 reais (~£5,500!) of

income per month. Indeed, a kind of middle class has emerged within the favelas.

Most of them have water (the blue tanks you can see on the top of each

building) and electricity, although the electrics are essentially an

incomprehensible mass of wires so tangled that only the bravest repair person

would dare go near them. The minimum wage is the equivalent of about £150 per

month, which is one factor in why drug crime managed to become so rife –

children under the age of 18 cannot be sent to jail, and once they reach 18

their records are wiped clean. They can live a life with impunity, making them

the perfect vehicle for transporting drugs around. The government is being

lobbied to change the law, but it’s a slow process.

Rocinha was pacified in November 2011 and it’s safe to walk

around. Safe, but not easy – there’s one main road winding its way through the

favela because it was built on the side of an old Formula 1 track. Other than

that, the only way around is through a labyrinth of alleys separating the

thousands of buildings. I don’t have the best sense of direction (or any, in

fact) as anyone who has watched me trying to drive somewhere without a sat nav

can attest. Or even with one. So without a guide, it would be insanely easy to

get lost. The residents are incredibly resourceful and artists have used things

like discarded magazines and even old records to fashion colourful artwork to

sell. Little goes to waste here.

The second favela we visited was Vila Canoas, a much smaller

dwelling with around 3,000 residents. Many favelas border rich neighbourhoods,

and this is no exception – the start of the favela on one side faced a row of

Brazilian mansions on the other. Favela residents often work for the wealthier

populace, so proximity to their workplace is important. Marina took us to a

school set up by the owner of the Fiat car company, who wanted to give

something back to the community. Para Ti has classes for favela children

(private schools for the rich kids – such as a nearby American school which

charges $6,000 entry and a further $2,000 per month – are clearly beyond the

price range of the locals), and they are available every day. There’s a

playroom and even yoga classes; a lot of kids have rough upbringings which then

spills over into aggression at school, so yoga helps dissipate this. It’s a

great idea – I wonder if it’d ever catch on in the UK. Whilst we were looking

around the school, we got the chance to try a homemade brigadeiro (chocolate

truffle) and it was divine.

I left the favelas feeling a little more optimistic. A lack of money doesn’t mean a lack of pride, and it’s clear that the people here are hard-working and resourceful. Their portrayal by the media has resulted in a stigma which is undeserved in most cases. The favelas aren’t going anywhere – there are too many people for that – but with the government now agreeing to hand out deeds for the land which the residents have built on, they may finally start getting acknowledged as a part of normal society, and in time, perhaps even absorbed into the wider Brazilian populace….assuming they decide they want to be.

We went for lunch in Cardamomo – a por quilo (per kilo) buffet restaurant that charges you a set amount

per 100g on your plate. They are stonkingly good value, and we loaded up our

plates for less than three quid each to see us through the afternoon. Back at

the hostel I almost had a breakdown when, after Windows decided to helpfully

dump a load of updates onto my laptop, it then failed to start up again. It was

completely dead. No lights, no power, nothing. Kaput. Four days into a

seven-month trip, brilliant. Thinking it may just be a case of overheating and putting

it out of my mind as best I could, we took a taxi to Pão de Açúcar – Sugar Loaf

Mountain. What should have been a fifteen minute drive from the hostel turned

into almost half an hour, as the main road along Copacabana beach was diverted for

reasons unknown, causing massive tailbacks and adding more stress to our

current mood. We finally pulled up outside and bought our tickets for the cable

car rides up which were valid at any point during the day, so we visited the

beach next to the entrance – Praia Vermelha. It was a lovely afternoon and great

for paddling, until the tide takes you unaware as Gilly found out…

Sugar Loaf is comprised of two viewpoints reached by two

separate cable cars – the lower one offers a good view on most days, but the

higher one is completely dependent on the weather. Amit had been a couple of

days earlier and said he could barely see a thing from the top due to cloud

cover. We managed to get lucky – not only with the weather, but also the

timing; we arrived about an hour or so before sunset, which meant that we got

to appreciate the view of Cristo Redentor bathed in wondrous colours as the

light faded, before appreciating Rio lighting up at night. I could have filled

an entire blog of photos from our trip up there but decided to pick a few (OK,

maybe more than a few) of my favourites to highlight the beauty of the place.

We somehow managed to find a bus back to Copacabana after

almost giving up searching for the bus stop. Our run of luck continued when we

got back and I decided to take the advice of a website I’d found and held down

the laptop’s power button for 30 seconds. I was rewarded with the power coming

back on – all was well again! Well, once Windows had sorted out the updates

which had knocked it out in the first place. Thanks, Microsoft.

The night was still young, and it was a Saturday, so we decided

to make the most of Rio’s nightlife and headed to Lapa. This is the party area

from Thursday to Saturday, and the bars are swarming with locals and tourists

alike. Getting off the metro station at Cinelandia and walking the

half-kilometre there can feel a little intimidating, as there are no shops open

and a lot of shady locals wandering around so going on your own may feel a

little risky, but we didn't have any issues. We immediately set about finding

food and beer, both of which were offered in abundance by the identikit stalls

that are set up by the arches. If you ever wanted to find a burger, caipirinha

or chicken on a stick, then this is the place to come – there are at least

fifty stalls. Gilly went for the chicken, I went for a burger, and Amit went

for a stick and a hot dog. In

hindsight, it would have been a good idea to do the same to soak up the

forthcoming alcohol, but you live and learn. After a couple of Antarctica beers

each, we took the advice of a hostel rep and sought out Bar da Cachaça where we had a shot of the eponymous spirit each - passion fruit for Gilly, açai for me, and chocolate with pepper for Amit. They were all pretty strong, and all delicious. A couple of craft beers (or what passes for craft beer in Brazil - it ain't Brewdog!) in another bar were followed by caipirinhas and shameless self promotion in Boteco da Garrafa, which in turn were followed by some sort of cocktails whose names escape me, in a bar whose name escapes me, which in turn were followed by some crazy dancing in a club which I have little recollection of entering. Nor, in fact, that of the taxi we took home at some crazy time in the morning.

My phone photos recall the later stages of the evening better than I do, but suffice to say it was a fantastic night, and Lapa is definitely a must-do for anyone looking to experience some of Rio's crazy nightlife.

My phone photos recall the later stages of the evening better than I do, but suffice to say it was a fantastic night, and Lapa is definitely a must-do for anyone looking to experience some of Rio's crazy nightlife.

No comments:

Post a Comment